The Charles S. Shultz House (Evergreens) is no longer open for tours.

Please see our blog post here for more information on the future of the house.

Charles S. Shultz House (Evergreens - 1896)

Built in 1896 by Hoboken Bank President Charles S. Shultz (1839-1924), this three-story home has 21 rooms, most of which have barely changed in the house’s history. The Charles Shultz House is representative of the new wealth flowing into Montclair during its railroad era transformation in the late nineteenth century from a predominantly farming community to a prosperous suburb.

In June 2019, the Montclair History Center (MHC) announced that we were at a crossroads regarding this property. You can read the article that appeared in the Montclair Local here and an Open Letter that appeared in the Montclair Local and was sent to our email list here.

For more information and to see more images of the house, read Cindy Schweich Handler’s article in Montclair Magazine, “Built to Last.”

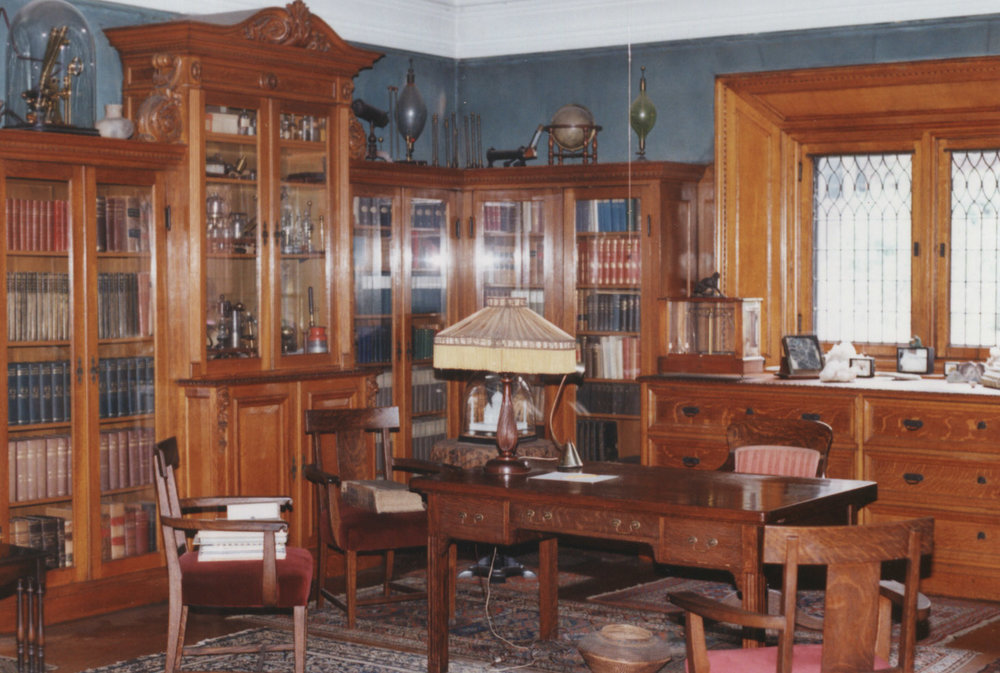

Charles Shultz's Library in 1897

The Shultz Family

Charles Solomon Shultz (1839-1924), a President of the Hoboken Bank for Savings, and his wife Lucy Murrell Budd (1844-1905), bought a two and a half acre parcel on the southwest comer of Claremont and North Mountain Avenues on March 1, 1894. Shultz commissioned his good friend and New York architect Michel Le Brun (1856-1913) to build a mansion on this property.

When the house was completed in 1896, Charles, Lucy, and their three children moved in. Charles Shultz’s wife Lucy passed away in 1905. Their children Emily, Walter and Clifford were given equal shares of the property at the time of their father’s death in 1924. On December 31, 1926, Walter and his wife Anna conveyed their one-third interest in the property to Clifford and Emily. In 1931, Clifford then transferred his one-half share in the property to his wife, Florence O’Neill Shultz. In 1952, Emily Budd Shultz transferred her one-half share in the property to Marian (Molly) Shultz. Molly therefore acquired the full share of the property at the time of her mother Florence’s death in 1962.

The Charles Shultz House remained in the family until it was bequeathed to The Montclair Historical Society in 1997 by Molly Shultz, who was also an active member. Having been home to three successive generations of the Shultz family, the house is a remarkable time capsule of 20th century life. Unlike other examples of late nineteenth century residences in Montclair, Evergreens retains nearly all of its original architectural detail, furnishings, and mechanical systems. Few alterations or additions have been made. In 1979, Evergreens was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Architects

The Evergreens was designed by one of New York City’s premier architectural firms, Napoleon Le Brun & Sons. The firm was known principally for its designs of Catholic churches, firehouses for the New York Fire Department, and commercial buildings. The twenty-one room house is one of the few examples of residential work on this scale by architect Michel Le Brun. It was Michel who built the still-standing Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower in New York City, which was the tallest building in America from 1909 until 1913. One of the reasons Le Brun received the commission for designing the Evergreens was because of his successful work with Shultz in designing the Hoboken Bank for Savings in 1890. While working on the design and construction of Evergreens, Le Brun’s heart was won over. He and his wife Maria Olivia moved to a house just one block away from the Evergreens at 8 South Mountain Avenue in 1896.

Charles Shultz's Library today

The Exterior

Also known as the “Evergreens,” the house got its nickname from the numerous evergreen trees existing around the property’s picturesque landscape. Its forty-foot height gives the house a commanding presence on the hill, and provides for a magnificent, unobstructed view of New York City.

Le Brun, in collaboration with the well-traveled Shultz, drew on a variety of sources for his design. Shultz was eager to incorporate half-timbered walls and red tile roofs, which he admired while in Europe during 1894. Working within the parameters set by Shultz, Le Brun came up with a scheme that was quite fashionable for the period.

The house is defined by its tall windows, which are larger on the lower floors and smaller on the top floors, further accentuating the verticality of the structure. The facade, with its formal center entrance, is balanced but not perfectly symmetrical. The long horizontal line of the veranda, interrupted only by the arched hood detail over the central entrance, adds to the perceived symmetry of the house.

The exterior is ordered by asymmetry, giving the structure character in its complexity. The solid proportions of the house are weighty, and the high gables, molded chimneys, gingerbread-decorated dormers, finials, and cresting along the roof deck give the building a great variety of outline, contributing to the overall intricacy of the house. Shingles cover much of the outer wall area. The veranda, the bay windows, and the rooftop deck effectively connect Evergreens to its picturesque setting.

Interior

The residence consists of the main building with the principal living spaces and bedrooms, and a rear kitchen extension. The first floor features an entrance hall in the center with other primary rooms grouped around it. Each room that spins off this hallhas a unique shape and character. Partly due to Shultz’s fear of fire, the interior walls on the first floor are masonry. All visible timber is chestnut.

Due to Shultz’s fascination with science, the house incorporates what was at the time state-of-the-art technology. It was built with gas/electric lighting fixtures, an electric burglar alarm, an enunciator system, an elevator, an advanced gravity hot air heating system, the latest plumbing, and an icebox that could be supplied with ice from the outside without entering the house. While he was eager to incorporate the latest technology, Shultz was also methodical and prudent, characteristics which also helped to shape the design of his house. Contingencies and safety measures were built into the house. Rather than be entirely dependent on electricity, combination gas/electric fixtures were installed in case the electrical system, still in its fledgling state, should fail.